About the Kan’ei Gyoko

(Imperial Visit to Nijo Castle in 1626)

The Kan’ei Gyoko—the Imperial Visit to Nijo Castle in 1626—took place over five days from September 6 to 10, when the Tokugawa shogunate welcomed the Emperor to Nijo Castle as an honored guest. Held only eleven years after the Toyotomi clan fell in the Summer Campaign of Osaka, the visit signaled reconciliation between the Emperor and the shogunate and proclaimed the arrival of peace throughout the land.

Over the course of the five-day visit, the Emperor was received with the finest hospitality of the age: exquisitely appointed reception rooms, lavish banquets, performances of court music and dance (gagaku and bugaku), Noh theater, and elegant pastimes such as waka poetry and instrumental music (kangen).

The imperial party included Emperor Go-Mizunoo; his consort, Empress Masako (Chūgū), a daughter of Tokugawa Hidetada; other members of the imperial family; and court nobles. On the shogunate side, under the third shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu, nearly eighty percent of Japan’s 230 feudal lords (daimyō) are said to have taken part in this grand occasion.

Schedule and Hospitality during

the Five Days of the Kan’ei

Gyoko

(September 6–10, 1626)

Day 1 of the Kan’ei Gyoko

(September 6, 1626)

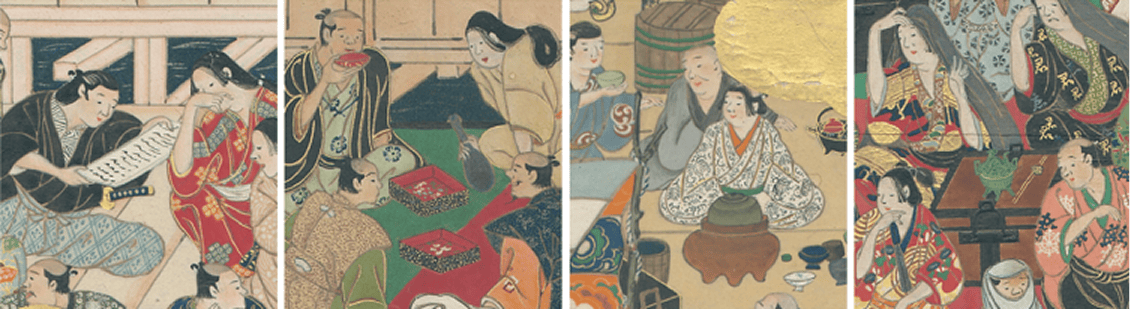

Detail from the Nijo-jo Gyoko-zu Byobu (Folding Screens Depicting the Imperial Visit to Nijo Castle), Edo period — Designated a Cultural Property by the City of Kyoto. Courtesy of the Sen-Oku Hakuko Kan Museum.

At the invitation of Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu, an unprecedented grand procession of more than 9,000 participants escorted Emperor Go-Mizunoo—the 108th emperor, often regarded as a central figure in the flourishing of Kan’ei culture—from the Kyoto Imperial Palace to Nijo Castle. The parade brought together both the imperial court and the Tokugawa shogunate, symbolizing a new harmony between throne and shogunate. The Nijo-jo Gyoko-zu Byobu (Folding Screens Depicting the Imperial Visit to Nijo Castle) shows how people of all ages and social ranks, drawn from across Japan, lined the route in their finest attire, transforming the day into a spectacular and historic occasion.

After the imperial party arrived at Nijo Castle, two banquets were held: Hare no Gozen, the formal celebratory banquet, and Uchi-uchi no Goen, a more intimate feast. The Emperor’s tableware was made entirely of gold, and other furnishings were arranged in sumptuous combinations of gold and silver—an opulent “golden” display that underscored the prestige of the occasion.

Day 2 of the Kan’ei Gyoko

(September 7, 1626)

After the Asa no Gozen morning banquet, Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu presented an extraordinary array of gifts to Emperor Go-Mizunoo; his consort, Empress Masako (Chūgū); the Emperor’s birth mother, Chūkamon-in; and the two imperial princesses. The offerings included gold, silver, and precious fragrant woods, with the silver alone said to have totaled 55,000 ryō. Later, court nobles (kuge) and feudal lords (daimyō) appeared before the Emperor, and performances of bugaku (court dance) were held.

Day 3 of the Kan’ei Gyoko

(September 8, 1626)

Kemari (a traditional court game) reenactment at Nijo Castle during the 2016 Sport,

Culture and

World Forum.

Photo: Yukishiro Daido

After the Asa no Gozen (morning banquet), Tokugawa Hidetada, the retired shogun (Ōgosho),

again

presented gifts, as he

had on the previous day: 2,000 ryō in gold to the Emperor, and a total of 25,000 ryō in silver to Empress

Masako

and

other members of the imperial household. The day’s program then continued with an equestrian demonstration

presented for

the Emperor’s viewing, followed by a kemari performance—the traditional court ball game. In the evening, a

waka

poetry

gathering was held, and the Emperor enjoyed gagaku (court music), including instruments such as the shō

mouth

organ and

the hichiriki reed

pipe.

At one point, Emperor Go-Mizunoo also ascended the tenshu (castle keep) of Nijo Castle. The Tokugawa jikki

records that,

because this was decided at short notice, red carpets were hastily laid along the passageways and blinds

were

hung in

the tower openings, allowing His Majesty a brief view in all directions. The weather that day, however,

appears

to have

limited the view.

Day 4 of the Kan’ei Gyoko

(September 9, 1626)

After the Asa no Gozen (morning banquet), a performance of sarugaku (Noh) was held—an art that, in the Edo period, came to be regarded as the Tokugawa shogunate’s official ceremonial performing art. From the Sengoku (Warring States) period onward, sarugaku was closely associated with auspicious occasions; it is said, however, that it was around the Kan’ei era that Noh became a regular feature of formal ceremonies at both the imperial court and the shogunate.

Final Day of the Kan’ei Gyoko

(September 10, 1626)

Kemari (a traditional court game) reenactment at Nijo Castle during the 2016 Sport,

Culture and

World Forum.

Photo: Yukishiro Daido

The final day began with Shichi-go-san no Gozen, followed by the presentation of horses from

Tokugawa Hidetada, the

retired shogun (Ōgosho), and Shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu to the Emperor and members of the imperial household.

During the

Three-Cup Ceremony (Sankon no gi), the Emperor is said to have personally poured sake for Hidetada and

Iemitsu—an honor

known as tenjaku (imperial pouring).

Around midday, the Emperor once again ascended the tenshu (castle keep) of Nijo Castle. The Tokugawa jikki

records that

he did so in hopes of a clearer view, since rain and low clouds on the previous day had obscured the

distant

mountains.

In the afternoon, the imperial party returned to the Kyoto Imperial Palace, and the magnificent five-day

series

of

ceremonies and celebrations drew to a close.

Key Figures of Kan’ei Culture

This section introduces the central figures of the Kan’ei Gyoko and other key individuals who shaped the culture of the Kan’ei era.

The Emperor of Cultural Flourishing

Emperor Go-Mizunoo

Emperor Go-Mizunoo was a distinguished cultural patron, well versed in scholarship and the arts, including

waka

poetry,

calligraphy, and kadō (flower arrangement). He commissioned the construction of the Shugakuin Imperial

Villa and

extended protection and patronage to many leading cultural figures, among them Hon’ami Kōetsu.

Only

three

years after the Kan’ei Gyoko, however, relations with the Tokugawa shogunate deteriorated, and he

abdicated

at the age of thirty-four. He then went on to exercise influence through insei (cloistered rule) for the

next

fifty-one

years.

A Bridge Between Court and Shogunate—and a Fashion Trendsetter

Tokugawa Masako (1607–1678), Empress Consort (Chūgū) (later known as Tōfukumon-in)

Tokugawa Masako, the fifth daughter of Tokugawa Hidetada, entered the imperial court at the

age of

fourteen to marry

Emperor Go-Mizunoo. Later known by the honorary title Tōfukumon-in, she played a key role in bridging

relations

between

the imperial court and the Tokugawa shogunate

A noted patron of refined and lavish design, she placed numerous orders with Karigane-ya, a Kyoto kimono

merchant. The

dyed textiles she commissioned became models for court style and helped popularize goshozome—designs

inspired by

the

colors and patterns associated with the Imperial Palace.

Completing the Foundations of Tokugawa Rule as Ōgosho

Tokugawa Hidetada(1579–1632), Second Shogun of the Tokugawa Shogunate

Tokugawa Hidetada helped solidify Tokugawa rule by issuing key legal codes such as the Buke Shohatto (Laws for the Military Houses) and the Kinchū narabi ni Kuge Shohatto (Laws for the Imperial Court and Court Nobility). At the age of forty-five, he ceded the title of shogun to his son, Tokugawa Iemitsu, and became Ōgosho (retired shogun), yet he continued to wield substantial political authority for years thereafter.

A Young Leader Guiding an Era of “Peace”

Tokugawa Iemitsu(1604–1651), Third Shogun of the Tokugawa Shogunate

Tokugawa Iemitsu, the second son of Tokugawa Hidetada, completed the bakuhan system through a firm, military-centered style of governance that imposed strict regulations on both the daimyo and the Imperial Court.He was also fond of chanoyu (the tea ceremony) and at times hosted tea gatherings on an impressive scale.

A samurai, a tea master, and a master of architectural design— the principal figure behind the Kan’ei Gyoko (Imperial Visit to Nijo Castle in 1626).

Kobori Enshu(1579–1647)

He served as Fushimi Bugyo (Magistrate of Fushimi) under the Tokugawa Shogunate. A man of remarkable versatility, he oversaw the construction of the Dairi (Imperial Palace) and the Sento Gosho (Palace of the Retired Emperor) in his capacity as Sakuji Bugyo (Commissioner of Construction). He also directed the major Kan’ei-period renovation of Nijo Castle, including the remodeling of the Ninomaru Garden. Renowned as a tea master, his style of tea ceremony came to be known as kirei-sabi, or “refined simplicity.”

Shōkadō Shōjō / Hon’ami Kōetsu / Kanamori Sōwa / Itakura Katsushige / Itakura Shigemune / Maeda Toshitsune / Hosokawa Sansai (Tadaoki) / Takuan Sōhō / Ishin Sūden / Hōrin Jōshō / Gesshū Sōgan / Tawaraya Sōtatsu / Nonomura Ninsei / Kanō Tan’yū / Ikenobō Senkō II / Sen Sōtan / Karasumaru Mitsuhiro

Banquets and Cuisine of the Kan’ei Gyoko

The cuisine that welcomed Emperor Go-Mizunoo at Nijo Castle was honzen ryōri, a formal multi-course style of dining central to court and warrior-class ceremonies of the time. This style combined the ceremonial elements of daikyō ryōri (grand banquet cuisine) with the refined techniques of shōjin ryōri (Buddhist vegetarian cuisine). It was organized into two main components: kenbu, centered on the serving of sake, and zenbu, which emphasized the meal itself.

Culture Following the Kan’ei Gyoko

Emperor Go-Mizunoo was a highly cultured ruler who valued scholarship and excelled in the arts, including

chanoyu (the

tea ceremony) and rikka (a formal style of flower arrangement). During the Kan’ei period, a number of

cultural

salons

formed around him, where participants refined both their learning and their aesthetic sensibilities.

The culture nurtured in these salons—gatherings that transcended social rank—would later have a profound

influence on

Japanese culture.

Detail from the Nijo-jo Gyoko-zu Byobu (Folding Screens Depicting the Imperial Visit to Nijo Castle), Edo period. Designated a Cultural Property by the City of Kyoto. Courtesy of the Sen-Oku Hakuko Kan Museum.

Transforming Nijo Castle to Welcome the Emperor: The Grand Kan’ei Renovation

The cuisine that welcomed Emperor Go-Mizunoo at Nijo Castle was honzen ryōri, a formal multi-course style of dining central to court and warrior-class ceremonies of the time. This style combined the ceremonial elements of daikyō ryōri (grand banquet cuisine) with the refined techniques of shōjin ryōri (Buddhist vegetarian cuisine), and is said to have been organized into two main components: kenbu, centered on the serving of sake, and zenbu, which emphasized the meal itself.

Nijo Castle was originally built in 1603 (Keichō 8) by order of Tokugawa Ieyasu. This first “Keichō Nijo Castle” is thought to have consisted only of what is now the Ninomaru Palace, surrounded by a single moat, with a five-story tenshu (castle keep) at its northwest corner.

In preparation for Emperor Go-Mizunoo’s visit, Tokugawa Hidetada, the retired shogun (Ōgosho), and Tokugawa Iemitsu, the third shogun, greatly expanded the Keichō-era castle. They extended the grounds westward, built a Honmaru Palace as Hidetada’s residence, and added an additional moat. South of the Ninomaru Palace, they constructed buildings for the imperial visit, including the Gyoko Palace and the Chūgū Palace. The castle keep built under Ieyasu was relocated to Yodo Castle, and a five-story tenshu from Fushimi Castle is said to have been installed in its place.

Iemitsu’s residence was the Ninomaru Palace, which still stands today and is designated a National Treasure. Approximately one thousand shōheki-ga (wall paintings) by the Kanō school continue to shine with undiminished brilliance. The gardens, too, were redesigned to be admired both from the Ninomaru Palace and from the Gyoko Palace, completing an elegant setting for imperial hospitality. This is the prototype of Nijo Castle as we see it today.

This Grand Kan’ei Renovation took nearly two years to complete. The figure who may be called its driving force was Kobori Enshū—a daimyō, tea master, and master garden designer.

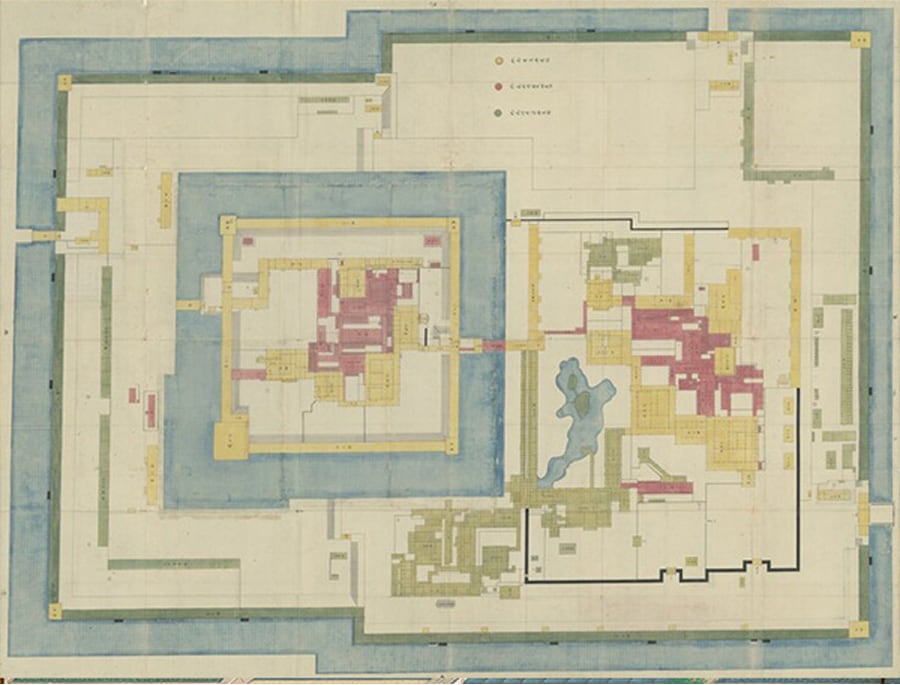

Nijō Gojōchū Ezu (Map of the Nijo Castle Complex), in the collection of Kyoto University Library.

This plan of Nijo Castle, thought to date from 1843 (Tenpō 14), shows the castle’s layout in detail. The Gyoko Palace is shown at the bottom, the Ninomaru Palace on the right, and the Honmaru Palace on the left, each distinguished by color. The sections marked in green indicate buildings constructed for the Kan’ei Gyoko that were later relocated or otherwise repurposed.

Preserved and handed down to the present day, Nijo Castle retains an exceptional architectural legacy. The Ninomaru Palace, designated a National Treasure, is the only surviving shogunal palace remaining in a Japanese castle. Many structures dating from the Grand Kan’ei Renovation also remain, including the Karamon Gate, the East and North Ōtemon (main gates), and the southeastern and southwestern corner turrets (yagura). In 1994 (Heisei 6), Nijo Castle was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Nijo Castle today — Ninomaru Palace (National Treasure) Courtesy of the Nijo Castle Administration Office